Ready for the future? Navigate NPPF reforms with Tyler Grange

16 Dec 2024

16 Dec 2024

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) guides development across England.

This reform could open new doors, especially where nature recovery meets climate adaptation and city building. Here’s our breakdown on the upcoming shifts and how they might play into your projects.

One of the most significant aspects in the proposed NPPF revision is the concept of Grey Belt land. Chapter 13, which focuses on Green Belt protection, has seen significant changes.

The update emphasises the priority of developing brownfield sites but introduces Grey Belt as the next option. This term describes land that only marginally contributes to the five purposes of the Green Belt but isn’t situated in areas of high environmental value, like Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) or National Parks.

This change prompts some big questions: Does the reform go far enough, and how will this new grey belt classification impact development decisions?

One concern is that focusing on Green Belt, including grey belt areas, might overshadow other vital factors such as landscape quality and biodiversity. While prioritising brownfield sites isn’t a new strategy, introducing the Grey Belt risks placing too much emphasis on Green Belt status at the expense of ecological value.

Saying that, the December version includes a notable addition from the September consultation in the ‘Golden Rules’ set out in paragraph 156. Part c and the related paragraph 159 put the strongest emphasis on the provision of high quality ecological landscape and open space improvements of any version of the NPPF or PPG3 before it.

Paragraph 155 sets a new, higher bar for releasing Green Belt land. Now, it must be shown that such a release wouldn’t “fundamentally undermine” the Green Belt’s function across the entire plan area. This shift focus from local changes to a broader perspective, raising the standard for what counts as harm.

It ensures a more predictable and strategic framework for development near Green Belt areas. With the higher threshold for releasing Green Belt land, there are clearer criteria to meet, which can help in planning and proposing developments. This means that our clients can be more confident in their investment decisions, understanding the stricter regulations mean fewer unexpected changes.

The guidelines also discourage ‘haphazard’ releases, promoting a more strategic approach. This could help reduce the piecemeal Green Belt releases we’ve seen before.

There’s promising language around improving public greenspace and the new paragraph 159 places much more explicit requirements for the improvement of not only open space but also landscape setting and ecological improvements, where potential has been within Local Nature Recovery Strategies. But this does open doors for our clients to show off their enhancements in public space provision.

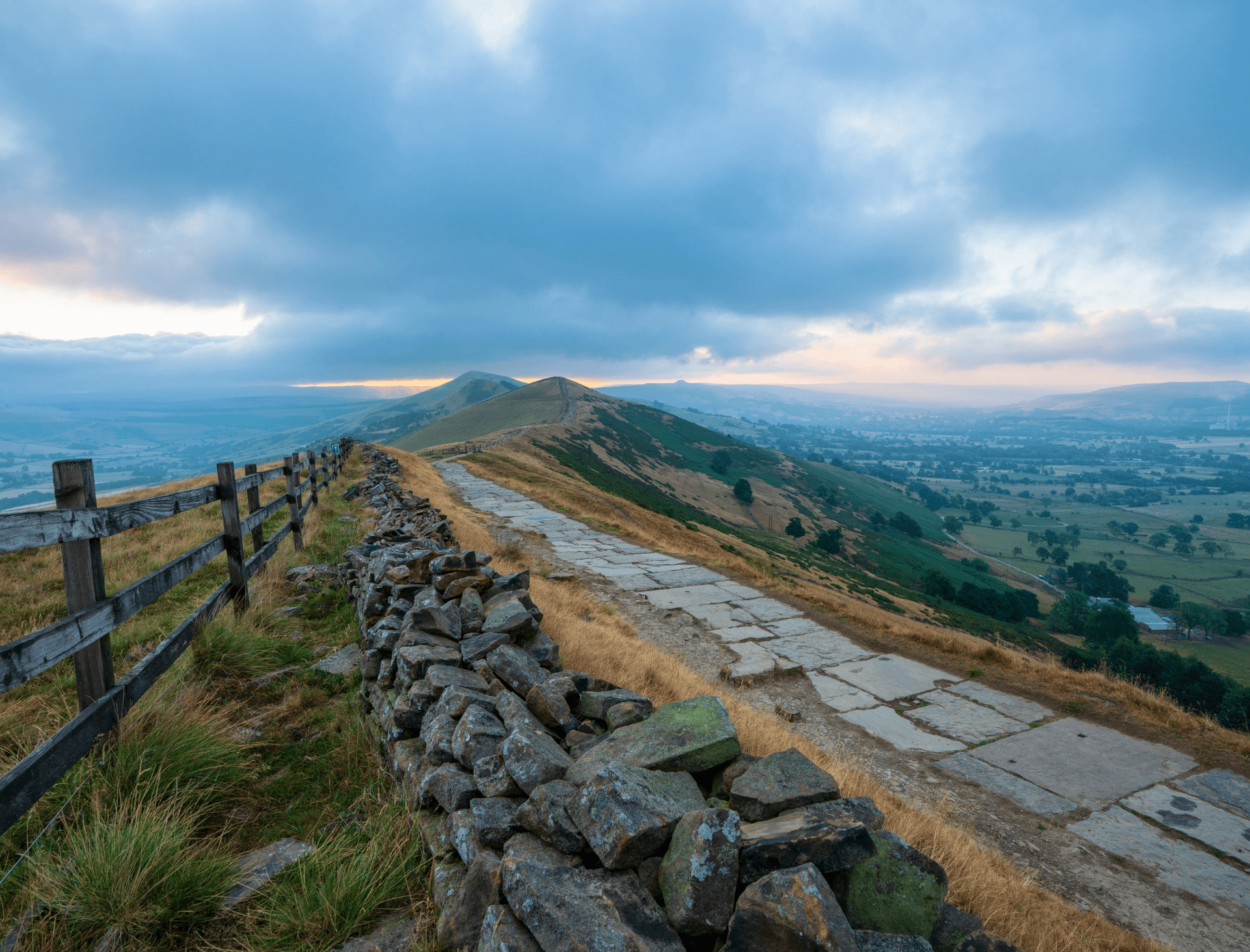

Also, the reform creates big opportunities to bring together nature recovery and climate adaptation efforts. Sites near urban areas and connected to larger green spaces are crucial for tackling climate issues like heat, air quality and water problems, including managing stormwater, building drought resilience and conserving water. This focus on climate resilience and ecosystem services, although new to the original Green Belt criteria, is now acknowledged as a priority in many areas.

Climate and nature recovery need a big-picture approach and a solid plan. The reform’s reference to the role of accessible green infrastructure – in promoting healthy communities, addressing identified local health needs and contributing to air quality and sustainable transport coupled with a focus on the ability of green infrastructure to provide multiple environmental benefits, is a welcome step. It shows we’re getting better at seeing how individual development sites fit into the wider collective response to climate change and the push for enhanced biodiversity.

As anticipated, the reform signals a renewed support for onshore wind farms. At Tyler Grange, we’re ready to jump in with these projects, leveraging our broad experience across England and Wales.

In terms of biodiversity, the commitment to mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) stands firm. Some strategic direction to this is now included in para 159 where it states that the new Golden Rules should contribute to Local Nature Recovery Strategies.

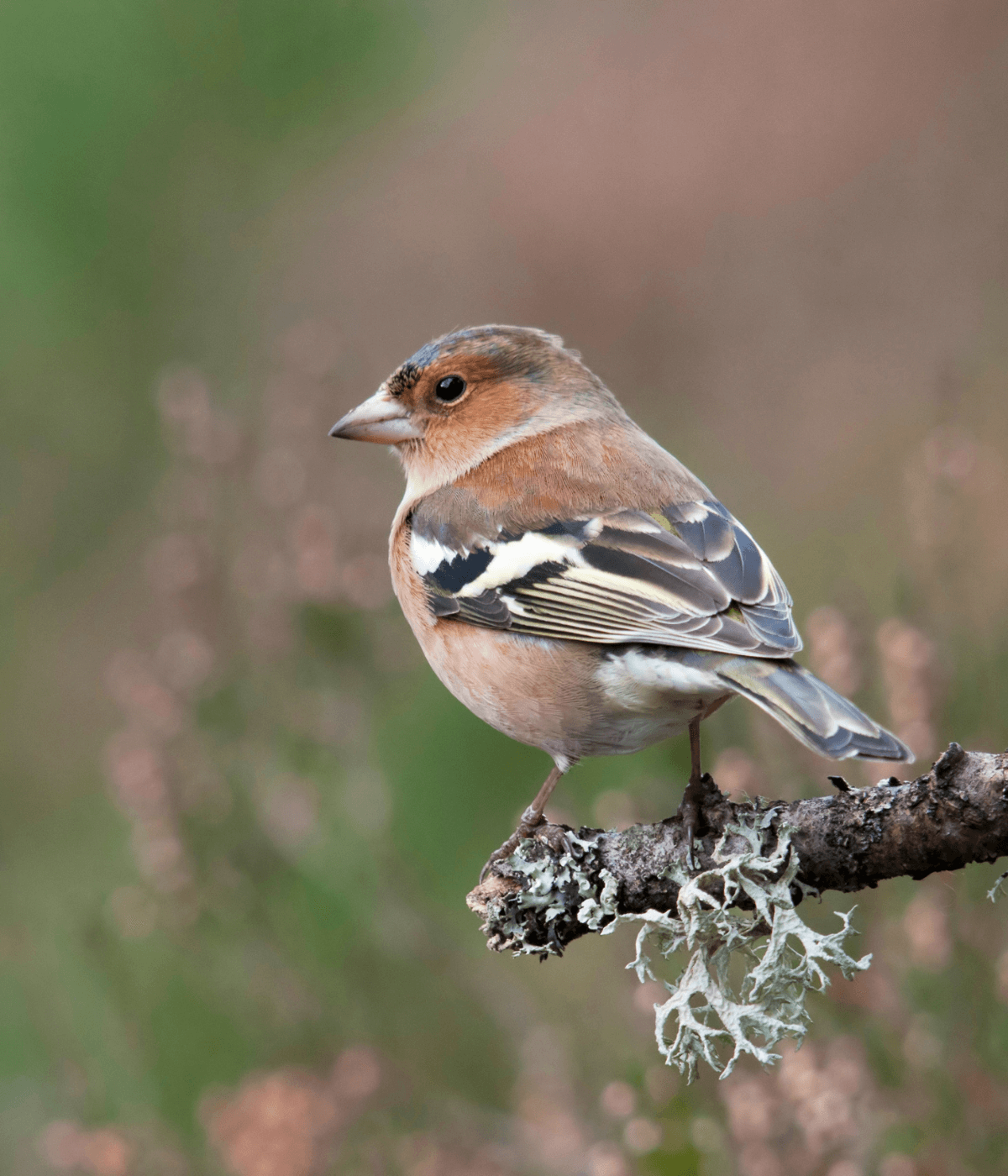

As part of creating biodiversity gains and ecological enhancements, reference is now made in para 187 to incorporating features which support priority or threatened species such as swifts, bats and hedgehogs.

Much bigger news on the horizon that has not made this version of the NNPF is the mooted relaxing of the Habitats Regulations to remove the planning backlog caused by habitats sites and protected species. This is something that was attempted by the previous Government, and which has predictably been raised again today by the incumbent in its development and nature recovery white paper, as part of its proposed planning reform and its “commitment to prioritising outcomes over process”.

Arguably the solutions to the backlog exist already and the issue is more one of resourcing and lack of capacity. If successful this time, changes to the Regulations will send major ripples through the industry and could potentially weaken protections and nature’s recovery. We will watch with interest!

The text content on arboricultural matters remains aligned with previous guidelines. Section 12, Para 136 of the NPPF highlights trees’ important roles in urban quality and climate change mitigation. The policy aims to ensure new streets are tree-lined and incorporates trees in new developments. There’s also a strong push for long-term maintenance plans for newly planted trees and retaining existing ones wherever possible.

The NPPF still includes a clear definition of ancient and veteran trees in Annex 2 within the Glossary, unchanged: a tree is termed ancient or veteran based on its age, size and condition. It must meet all three criteria to be categorised as such. This precise definition is vital for consistent identification and preservation efforts.

Here’s a twist: the definition of veteran trees isn’t uniform across all documents, leading to a bit of a head-scratcher in identification during new developments. At Tyler Grange, we cut through the confusion with a tight-knit, cross-discipline approach to keep our tree ID and veteran tree classifications robust and always with the NPPF policy implications in mind.

The status of ancient woodland, along with ancient and veteran trees, remains firmly planted as irreplaceable habitats. Para 193, item ‘c,’ lays it out: any development that risks these habitats should be a no-go unless there are wholly exceptional reasons and a suitable plan for compensation exists. Examples of such extraordinary cases might include essential infrastructure projects where the broader public good clearly overshadows the environmental downsides.

While our approach to tree policies and assessments with the NPPF might seem like “business as usual,” we’re actually branching out. The increased demand for skilled arboricultural consulting, driven by a surge in housing developments and renewable energy initiatives, has prompted us to expand our team and enhance our expertise. We’re digging deeper into these complex issues — expect to hear more about our growth and initiatives soon.

The proposed NPPF reforms introduce encouraging updates, especially by highlighting the diverse benefits of Green Belt releases. The reforms also make significant strides by weaving climate adaptation and nature recovery into strategic planning.

But a lot of the essential details are tucked away in the accompanying notes rather than being front and centre in the main NPPF document. We’re hopeful these key points will be fully incorporated into the final version.

Tyler Grange is geared up for the shifts these reforms will bring. Curious about how these changes could impact your projects? Reach out. We’re here to help you steer through this changing terrain.